On Tuesday, June 14 at 8 p.m. Norwegian time, Canada, Denmark and Greenland signed a demarcation line agreement that resolves the long-standing border dispute between Canada and Denmark (Greenland).

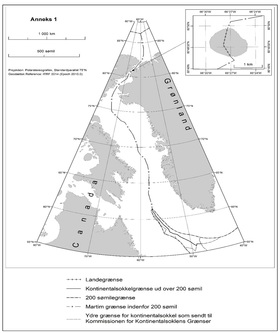

The agreement is a comprehensive agreement that involves a solution to the sovereignty dispute over Hans Øy and provides for a final delimitation of maritime areas within 200 nautical miles in the Lincoln Sea northwest of Greenland and the Labrador Sea southeast of Greenland. West Greenland.

In accordance with the law of the sea

It follows United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea that States are free to agree on how they wish to establish the geographical demarcation between them and that the main objective is to reach a fair and reasonable solution. Beyond that, the Convention on the Law of the Sea sets no further guidelines on how the limit should be determined. Through case law, however, a three-step model for maritime demarcation has been developed. This model is based on a mathematically calculated median line, measured from the coast of each of the states. The median line is then adjusted in light of other factors that the parties consider relevant to the boundary.

These relevant factors may be, for example, geographical factors, such as the design of the coastline and the presence of islands. There may also be non-geographical factors that come into play, such as the economic activities and interests of the parties in the region.

After the mathematical center line has been adjusted in the light of the relevant factors, a so-called proportionality test is finally carried out, in which it is examined whether the adjusted center line could lead to an unreasonable or unfair result for one of the parties, among other things with regard to the ratio between the length of the coastline of each of the countries and the size of the maritime area they delimit at the border. Although the three-step method is primarily developed for use in cases where the boundary dispute is to be decided in court, in practice it is also often used by states negotiating an out-of-court boundary line agreement.

A final solution to the whiskey war

Hans Øy is a 1.3 square kilometer uninhabited limestone island located in the Kennedy Channel in northwest Greenland. When Canada and Denmark (Greenland) signed a treaty in 1973 defining the boundary between them in the Kennedy Channel, they failed to agree on who had sovereignty over the island. The 1973 delimitation agreement therefore explicitly stipulates that there is no border between border points 122 and 123, where Hans Øy is located.

The island has been the subject of the so-called “Whiskey War” since 1984, when Canada planted a flag on the island and left behind a bottle of Canadian whiskey. When Tom Høyem, Minister of Greenland, visited the island later that year, he planted a Danish flag and left behind a bottle of Danish schnapps and a letter saying “Welcome to Danish Island”. Despite the humorous tone, the parties have not been able to agree on sovereignty over the island in the past.

The island itself has little economic value, and since the maritime zones of the parties in the Kennedy Channel were established as early as 1973, the division of the island does not have much real significance. However, the Kennedy Canal could be of interest to international shipping if global warming allows new shipping routes to the Arctic Ocean.

In the border agreement signed on June 14, the parties finally agreed on the sharing of Hans Øy. The negotiations took place behind closed doors and we do not necessarily know which considerations the parties placed decisive emphasis on. By convention however, Hans Øy is split in two between Denmark (Greenland) and Canada. The boundary is apparently drawn along natural gorges on Hans Øy, a method of division which we recognize from both the Law of the Sea and other land disputes, and it gives Denmark (Greenland) sovereignty over a slightly largest on the island. With this, Canada gained its first land border with Europe.

79,000 kilometers2 with overlapping requirements

In addition to finally finding a solution for Hans Øy, Canada and Denmark (Greenland) have also made the final demarcations between themselves in the sea areas southwest and northwest of Greenland, where they have no failed to reach an agreement in the 1973 agreement.

According to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, coastal states have the right to establish an economic zone off their coasts, extending up to 200 nautical miles from the baseline. Moreover, States’ right to the continental shelf may extend well beyond this distance. In the Labrador Sea, which lies between Newfoundland and Labrador in Canada and Greenland, this meant that Canada and Denmark (Greenland) had overlapping requirements in an area of up to 79,000 square kilometres, an area that is now divided between the parties. .

The context of the chosen solution is not communicated by the parties. However, the official map indicates that the boundary was drawn on the basis of the median line principle, with some adjustments which safeguard the interests of the parties in the area and the relevant considerations. The division methodology appears to be consistent with case law and interstate practice.

Indications of the future division

Also to the north, Canada, Denmark and Greenland succeeded in establishing a common watershed in the Lincoln Sea. The border is based on a 2012 Interim Border Agreement, which is now included in the legally binding Boundary Line Agreement between Canada and Denmark (Greenland).

In the Lincoln Sea, the parties apparently referred to a mathematically calculated center line between the coasts of the states. This sends a very important political signal and indicates that Denmark (Greenland) and Canada intend to agree on a middle ground solution also further north in the Arctic Ocean, where Danish and Canadian shelf demands overlap Russia’s requirements for ownership of the seabed. .

Great geopolitical importance

The solution to the sovereignty dispute over Hans Øy is not only to determine where the border should go, but also to lay the foundations for broader cooperation between Canada and Denmark (Greenland), which is particularly important for the Inuit population of Nunavut and Greenland. The agreement on Hans Øy therefore has not only a symbolic value, but also a great practical and real significance. For this reason, cooperation between states is also explicitly included in the demarcation line agreement.

The border agreement is signed shortly after Canada, Denmark and five other Arctic states decided to resume Arctic cooperation in projects within the Arctic Council without Russian participation. At a time when international law is under pressure and when international law and treaties are constantly challenged, it is a positive sign and a clear signal that the Arctic states of Canada and Denmark (Greenland) are demonstrating a willingness to dialogue and the ability to reach solutions within the framework of the Convention on the Law of the Sea and in accordance with the Ilulissat Declaration of 2008.

The message was first published on UiT

“Web specialist. Social media ninja. Amateur food aficionado. Alcohol advocate. General creator. Beer guru.”