We live in a part of the world that is strongly characterized by a violent geological period – the end of the last ice age.

This ice age began over 100,000 years ago and reached its peak around 20,000 years ago. At that time, among other places, all of Scandinavia and parts of Britain, Russia and North America were under thick ice.

In some places, including parts of Scandinavia, the ice could be more than two kilometers thick. All of the mountains and landscapes we would later live in were encapsulated in ice, and the landscape below was squeezed by the heavy ice cap.

Since the ice began to melt, the landscape has risen again. The uplift caused the sea to uplift what we now call the Norwegian landscape. It’s still ongoing, and parts of Norway are growing up to 1 centimeter a year, according to geoforskning.no.

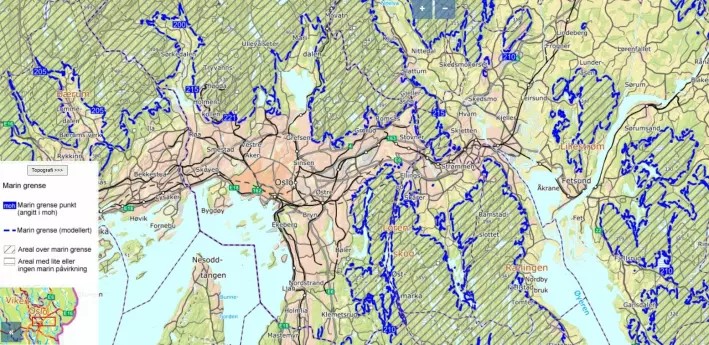

In some places in Norway and Sweden the country has risen several hundred meters since the Ice Age, and the old sea border was, for example, at Skådalen in Oslo, 220 meters above sea level. sea current.

Here you will find the loose mass map of the Norwegian Geological Survey (A G).

This long geological history is the direct cause of live clay – a geological phenomenon that causes problems in modern-day Norway, Sweden and Canada, Louise Hansen tells forskning.no. She is a researcher and sedimentologist at the Geological Survey of Norway (NGU).

We will come back to the exact reasons why it is mainly problematic in these countries.

– I had never heard of fast clay before moving here, Louise Hansen from Denmark, tells forskning.no.

Today, among other things, she helps map the ancient seabed with sea clay in Norway. There may also be fast clay.

And as the Gjerdrum landslide showed, living clay has a special property: it changes from quite solid to liquid when it is disturbed and affected too much. Then large areas can erupt, taking houses, fields and roads with them. Exactly how the Gjerdrum landslide was triggered is currently unknown.

Living on the old seabed

When the ice began to melt, major changes occurred that led to the landscape we know today.

And when the mile-thick ice melts, billions of liters of water are released into the sea.

– He blew monstrous amounts of water and clay into the fjords, Hansen tells forskning.no.

– This happened during dramatic changes in the climate and the landscape was changing violently. It was this period that largely laid the foundation for what we have now.

Much of the North Sea was also dry land as the ice retreated, and is now called Doggerland. You can find out more about this lost part of Europe at forskning.no.

The clay of the earth has formed thick layers in the salt water of the sea, and the salt of the salt water has become part of the structure of the clay. Hansen explains that the salt ions — electrically charged molecules — in the clay help bind it together and make it stable.

As Norway rose due to uplift and disappearance of the ice, this seabed was slowly lifted from the sea and became dry land. The rivers carved out the landscape, and it became the landscape we know, for example, in eastern Norway or in Trøndelag.

– These are areas that have good fertile soil, and there are flat areas where it’s easy to move around, Hansen tells forskning.no.

This ancient seabed is therefore attractive for us to live in – but in some places this clay has undergone a change: it has become fast.

Lose the salt

Hansen explains that this does not apply to all the clay on the old seabed, but in some places the change is happening: over thousands of years salt can be leached out of the clay, due to slow groundwater flow. This is how pockets of live clay can form.

That’s why it’s so important to conduct thorough surveys in areas of marine clays, to find out where these pockets may be, according to Hansen.

When the salt is leached out, the clay loses some of what holds it together. If there is some kind of load that the fast clay cannot withstand, it can turn into a liquid form. This is illustrated in the video below, where this collapse is shown.

NGI’s video shows the Rissa landslide in Trøndelag in 1978 and shows how a small landslide released a large pocket on the upper side with fast clay. Over 20 homes and one human life were lost in the landslide.

But even though the living clay has lost a significant part of its structure, it can still support a lot if left intact.

Hansen says large areas of fast clay can collapse if a single spot is stressed. A stream or river can, for example, trigger a small landslide down a slope, thus perforating a pocket of live clay. It can become a large, naturally triggered landslide, which is caused by erosion over a long period of time.

With construction and excavations there can also be heavy loads on the clay.

The Rissa landslide, for example, was triggered by backfill material from an excavation at a farm, and about half of all rapid clay landslides in the past 50 years in Norway have been triggered by human activity, which you can read more about at Forskning. .Nope.

This landslide was therefore triggered by a heavy mass that settled down to the edge of the water. When some of the clay near the water slid, more and more clay was stirred up and slid into the upper side area.

This is why it is also important to have an overview of the fast clay areas in the beach area, Hansen believes.

– This is a type of area that we also need to focus on, investigate and inform about, Hansen tells forskning.no.

She says fast clay can continue below the seabed and is therefore difficult to map.

Other places in the world

– In general, it is Norway, Sweden and Canada that have this problem, explains Louise Hansen to forskning.no.

Indeed, regions in these countries have experienced very similar geological development since the last Ice Age, and conditions have also been favorable for rapid clay formation.

In Canada, quick clay is called, among other things, Champlain marine clay, named after a large temporary sea that formed when the ice retreated and has long since disappeared. This sea stretched far into present-day Canada, above what are today cities like Ottawa, Montreal and Quebec.

Due to land uplift after the ice age, this sea receded, but left seabed on land similar to parts of Norway.

In 2010, for example, there was a large quicksand slide near the town of Saint-Jude, near Montreal, where four people died, according to the Canadian newspaper The Globe and Mail.

“Devoted reader. Thinker. Proud food specialist. Evil internet scholar. Bacon practitioner.”